The Role of Big Business in LGBTQ+ Politics, Pt. 2: The Master’s Tools and Jostling Anticapitalist Politics

In Part 1 of this post, I talked about my reading of Carlos A. Ball’s The Queering of Corporate America and many of the things I learned from it. I shared tools from our history that we can use to keep ushering our movements forward. It surprised me to see the multitude of ways big business had actually aided LGBTQ+ causes throughout American history.

In this second part, I’m shifting gears. First, I’ll explore in more depth some of the ways reading that book made me question my own anticapitalist politics. Then I’ll extrapolate on some of the dangers of relying on corporations. Making connections to the work of Audre Lorde, I’ll assert that working with corporations, while valuable, will never let us achieve liberation.

I do not want this post to lessen the value of anything I shared in the previous one. All of those statistics and strategies are still vital tools for us. But I want to be clear that, at some point, we can’t call corporations our friends anymore. We will never achieve true liberation while working with them.

Thoughts, comments, and questions are thoroughly welcomed on this post. I hope you enjoy.

Table of Contents

Jostling my own politics

If there’s one thing I’m certain of, it’s that no framework, however robust or ethical, works for everyone. I am, in most of my life, vehemently anti-Cure, but the work of Eli Clare, as well as the lived experiences of so many people, tells me that anti-Cure politics don’t sit right with everybody.

And I find the same with anticapitalist politics. Being anticapitalist is a tricky corner to occupy. On one side, you see that capitalism is a system of oppression and systematically reinforces many of the things you fight against. You know that you can never really “solve” those issues under capitalism.

It is also an inherently anti-queer system, as described in Sherry Wolf’s book Sexuality and Socialism:

“Capitalism creates the material conditions for [people] to lead autonomous sexual lives, yet it simultaneously seeks to impose heterosexual norms on society to secure the maintenance of the economic, social and sexual order.”

On the flip side? All of us (in America) live under a capitalist system, and to one extent or another, we have to cooperate with it to meet our goals and sustain ourselves. Where do you draw the line between working with and against capitalism? When is it ok to work within the system, and when is it not?

Ball’s book shifted my line at least a few feet. I understand a lot better how valuable corporations have been as LGBTQ+ allies. I am still anticapitalist. That’s not up for debate. But I’m more willing to accept, and see the value in, working within capitalist systems. It’s hard to have the resources to dismantle the system without first building those resources under the system.

I still believe that complete and total liberation will only occur with the destruction of capitalism—perhaps, in my personal beliefs, with the destruction of money economies entirely. However, using capitalist resources to fight against a capitalist system is still resistance, so long as you’re minimizing the benefits provided to the system.

This rethinking is important, and I’m very grateful that the book encouraged it in me. When we become too set in our belief systems, change stagnates. Without that change, there is no growth. To work toward liberation we must be willing to challenge, question, and change ourselves.

That’s why I shared so many of the examples and tools I did in the last post: because I believe they can be used for good. But for the rest of this post, I’m going to be focusing on the potential downsides of working within the system of capitalism, of calling corporations your friends. It’s vital that we understand all of the potential implications of our resistance. Both sides of the coin are true and exist at the same time: corporations are valuable allies, and they’re dangerous ones. Do with that contradiction what you will.

When corporations aren’t on our side

It should be noted that while big business was a crucial ally to the LGBTQ+ movement, it was not (and has not been) the same for other progressive causes. Access to reproductive healthcare, redistribution of wealth, and divesting from genocide have all been opposed by our corporate “friends,” among other issues.

(post continues below)

Want to receive once-a-month updates from me, directly in your inbox? Add your email below to subscribe to my newsletter. To prevent spam, you may get an email asking you to confirm your subscription.

It makes the world go ‘round (and my head hurt)

Money. The driving force behind all of humanity’s actions, the system necessary to allow global trade—or so Mr. Krabs would have you believe.

It is undeniable that in most cases, corporations chose to be LGBTQ+ allies because they knew that it was better for their bottom line. For at least the past century in the United States, big businesses have all shared that same common goal: increasing their wealth. In very rare cases, business truly became convinced that supporting LGBTQ+ rights was simply the right thing to do, regardless of money.

As was noted in Part 1, this wealth is part of what makes them such strong allies. They can use it, or withhold it, to affect change in a way many smaller groups and activists simply can’t. But it’s also what makes them dangerous, because the change they’re pushing for might not always be good for us. That’s what we’re seeing right now. Businesses are once again testing whether it might be more profitable to be against us than for us.

On top of pushing for explicit change, many large corporations also use their money to support political candidates that push anti-LGBTQ+ legislation and action. These same companies might later use their funds to protest that legislation. As Ball says on page 206:

“It is hypocritical for companies and their executives to strongly oppose anti-LGBTQ measures while simultaneously giving thousands of dollars to the political campaigns of the most important and vociferous proponents of those laws. By funding the campaigns of anti-LGBTQ politicians, such as those who supported the North Carolina bathroom law, corporations are doing nothing less than subsidizing bigotry and prejudice.”

One of the biggest issues with the power corporations have is a lack of oversight and restraint of that power, especially their financial power. In their 2010 ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, the Supreme Court functionally struck down nearly all limitations on corporate political spending.

This change has allowed organizations to funnel more and more money into influencing elections outside of directly supporting political candidates and their campaigns. It is based on an interpretation of the First Amendment in a debate that walks a very fine line between reasonable restraint and unreasonable censorship. As Ball says on page 199:

“In short, the Supreme Court committed a grave error when it held that the First Amendment does not permit campaign finance reforms that seek to limit the spending of corporate money to influence the outcomes of elections. However, it is a different matter altogether to contend that the First Amendment allows the government to limit the ability of corporations to speak on public policy issues—ranging from the desirability of government regulations that affect the private sector to the advisability of free trade policies to the appropriateness of anti-LGBTQ rights laws—in ways that do not call for the election or defeat of particular candidates for political offices.”

This lack of limitations, coupled with the causes big businesses have been supporting, has created an interesting disconnect. Conservative voices, usually proponents of corporate involvement in politics, have critiqued businesses for supporting LGBTQ+ causes, at times calling for more restraint.

Progressive voices, usually critical of corporate involvement, have instead embraced the support for LGBTQ+ rights, relaxing their pressure for control. In many ways, it’s similar to the internal debate I described above, the line between accepting help from businesses and not entirely supporting them.

Regardless of where you fall, it’s undeniable that corporations have massive amounts of political sway. And they aren’t always using that power for good.

The real toll of homophobic policies

Most queer and trans people are painfully aware of the toll that homophobic policies—governmental and corporate—take. We’ve lost people, or know someone who has. So I’ll just provide one example here, detailed on pages 75-80.

At the height of the AIDS crisis, Burroughs Wellcome was the first company to market a treatment for the condition, in 1987, called AZT. It was initially marketed at an annual price of $10,000, something that the majority of people could not possibly afford.

Of course, activists were outraged. Hundreds, if not thousands, of demonstrations happened across the country. Two of the most public were an invasion of Wellcome’s headquarters and a disruption of the NY Stock Exchange.

Eventually, in 1989, the price was reduced to $6,500/year. Still a massive sum.

In 1991, Bristol-Meyers Squibb marketed another drug (ddI) and learned from Wellcome’s mistakes. Their agreement contained stipulations to keep the price “reasonable” ($1,745/year in 1991), as well as providing the medication for free to those who couldn’t afford it. This agreement almost certainly saved lives.

There are two important takeaways from this all-too-common healthcare industry story. First, while the price was eventually lowered, the initial high costs and inaccessibility undoubtedly contributed to the death toll and suffering of the AIDS crisis. Burroughs Wellcome has blood on their hands.

Second, and perhaps more significant, this entire situation only occurred because of the capitalist healthcare market. The ability for a single corporation to hold the only treatment for an ailment, as well as to choose its price, is harmful. Private healthcare enabled the disparity that led to so much suffering. Not only Burroughs Wellcome, but the entire medical-industrial complex has blood on its hands, in this situation and so many more.

So while we can use the aid of corporations at times, relying on them forever will lead to more death, more disparity, and more pain.

We can’t use the master’s tools forever

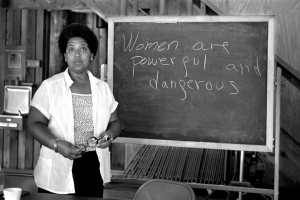

In 1979, Audre Lorde spoke (and later wrote) the words that would prove a needed wake-up call and constant reference in many humanities fields:

“For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support.”

While talking about feminism and the plight of women, Lorde’s words are applicable to so many systems of oppression. Indeed, intersectionality was vital to Lorde, and the lack of it was part of what spurred the rage behind these words.

What are the master’s tools?

In the case of big business and LGBTQ+ equality, the master’s tools are a combination of tangible and intangible resources used by corporations and activists alike. The master here, of course, is the cis-hetero-patriarchal system of capitalism we’re living under. (Sheesh, that’s a lot of hyphens for one word.)

Corporate money, policies, advertisements, and political pressure are all the master’s tools. So are government aid programs and other causes that encourage individuals to be reliant on governments or corporations.

Lobbying a business to support a political cause is a plea to be granted access to the master’s tools. The 400 signatures on the amicus brief of Obergefell v. Hodges were a weaponization of these tools.

In these moments, we temporarily beat big business at its own game. But as Lorde says, they did not bring about genuine change. As we continue to see, those legal decisions and business policies can be overturned. Genuine change is far more sustainable than that. But without those small victories, it can seem impossible to even imagine genuine change.

This fact may only be threatening to those LGBTQ+ folks who still rely on the master’s house—big business, government policies—as their main source of support. But can we blame those people—ourselves—for being in that scenario? I don’t have a good answer, for is the system not designed to put us in that position?

So what tools do we use?

It isn’t enough to just say, “we shouldn’t always rely on corporations!” Is it true? Yes. But without alternatives, it just leaves people feeling frustrated and hopeless.

In my own view, the genuine change our country needs is a complete rebuilding from the ground up. We cannot take a system built to oppress, a system built on enslavement and disenfranchisement, and make it better. But that kind of rebuilding is a monumental task, and truthfully, I don’t see it happening in my lifetime.

That doesn’t mean there’s no hope. There are still steps we can take.

One of the biggest is helping ourselves be less reliant on the support of the master’s house. The Disability Justice movement is a great source of inspiration here, promoting interdependence and networks of care. Many of us need to rely on the medical system to survive. But can we get other care—spiritual, emotional, nutritional, physical—from our communities, from the land?

An addition from Rachel: I saw a good video about this sort of shift recently that said: “Don’t eat the rich, starve them” and recommended as much as possible getting resources from outside of the capitalist system.

Another huge step is in education. Once again, a quote from Lorde:

“Women of today are still being called upon to stretch across the gap of male ignorance and to educate men as to our existence and our needs. This is an old and primary tool of all oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with the master’s concerns. Now we hear that it is the task of women of Color to educate white women—in the face of tremendous resistance—as to our existence, our differences, our relative roles in our joint survival. This is a diversion of energies and a tragic repetition of racist patriarchal thought.”

She said this nearly 50 years ago, but does it not ring true today? Is this “diversion of energies” not still a tactic employed to exhaust LGBTQ+ folks away from the fight for their own liberation?

This is where I’m calling not on LGBTQ+ readers, but on our allies: will you speak up in defense of us? Ask yourself, “how much am I promoting education about and wellness of LGBTQ folks? What’s stopping me from doing so?” If you’re not satisfied with your answers, there might be room for you to do more.

You don’t even need to speak for us. There are countless pieces of media, like Ball’s, we’ve created that can educate others. You only need to help connect them to it, take a bit of the weight off of our shoulders.

Lastly, perhaps one of the most radical things any of us can do is not give up. Even when we have to work within the system that’s pushing us down, even when we feel defeated, we can keep that spark deep down. It might need to rest for a while, but it can always be rekindled into a massive flame. We haven’t truly lost until we stop resisting.

Do you have other thoughts on LGBTQ+ rights and big business? More pieces of advice you want to add, or questions to ask? I’d love to hear from you! Let me know in the comments on this post if you’re so inclined.

Want to receive once-a-month updates from me, directly in your inbox? Add your email below to subscribe to my newsletter. To prevent spam, you may get an email asking you to confirm your subscription.

No Comments